COMMENTARY: Postcolonial and Decolonial Theory – Relevance to Antigua and Barbuda

15 December 2025

15 December 2025

By: Dr. Lenworth Johnson

To explore postcolonial and decolonial theory, it is essential to grasp what colonialism is. This is usually clear for countries and peoples that were previously or are currently colonized. Colonialism involves the conquest or negotiated takeover of territories, in which the colonial power imposes its laws, culture, and values on local populations. Over hundreds of years, European powers – also known as Western powers – driven by the search for resources, new markets, empire, and power, colonized Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Oceania, the Americas, and the Caribbean, leaving deliberate and lasting impacts on the mentalities and cultures of these regions. As Leela Gandhi succinctly states in Postcolonial Theory, A Critical Introduction, “colonialism marks the historical process whereby the ‘West’ attempts systematically to cancel or negate the cultural difference and value of the ‘non-West’.

Postcolonial theory aims to identify and understand the enduring impacts of colonialism on former colonies and their peoples. It is an academic framework that examines, explains, and questions the cultural, political, and economic legacies left by colonialism and imperialism. Developed in the late 20th century, especially following decolonization movements in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, postcolonial theorists analyze how colonial powers shaped societies, identities, and knowledge systems in formerly colonized regions, and how these influences persist even after independence. The theory often investigates how literature, art, and culture reflect and challenge colonial narratives. Influential thinkers like Edward Said (author of “Orientalism”) explore how language, representation, and power operate in the aftermath of colonial rule, emphasizing the need to critique Eurocentric perspectives and amplify voices from the Global South—such as Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. In essence, postcolonial theory explores the structures of colonialism that still exist today and their ongoing effects on us.

Decolonial theory aims to decolonize the mind, or “delink” from Western/European systems such as capitalism, Western/European ways of thinking and being (philosophy and ontology), and Western/European epistemology (the theory of knowledge, especially regarding how knowledge is established, its validity, and scope). Decolonization involves the recovery and validation of indigenous knowledges, practices, and other worldviews. The goal is not necessarily to move away from Western or Eurocentric philosophies and standards but to give other global philosophies, such as African and Asian philosophies, equal recognition in the realm of consciousness and thought. For example, besides Western scientists and philosophers like Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle, there is Egyptian Imhotep, Senegalese Cheikh Anta Diop, and Chinese Confucius. Key figures advocating for decolonial theory include Aníbal Quijano, Walter Mignolo, and María Lugones. The movement stresses epistemic justice, which means the right of marginalized and oppressed peoples to define their own ways of establishing knowledge and living. In sum, decolonial theory involves the efforts and methods to break free from the legacies and consequences of colonialism.

Politically, for example, Antigua and Barbuda maintains a colonial Westminster-style government, a constitutional monarchy based on the British system. (The term Westminster comes from the Palace of Westminster, the seat of the British Parliament.) The head of state is the Governor General, who is responsible to the Queen of England. The head of government is the Prime Minister, who is the political leader of the party with the most seats in the elected parliament. There is also an appointed Senate, which confirms legislation. Antigua and Barbuda gained independence from Britain on November 1, 1981. As our leaders are regularly elected, we call our country an independent democracy, but are we truly “independent” when our Governor General still reports to the British monarch? This writer argues no, and it is time for Antigua and Barbuda to move toward delinking politically from the United Kingdom (that is, abolish the position of Governor General), become a republic, and appoint or elect our own presidential head of state. Other Caribbean countries, such as Guyana and Dominica, have paved the way (most recently Barbados, which is now a parliamentary republic). While many colonial remnants will persist, this marks a step toward true decolonization.

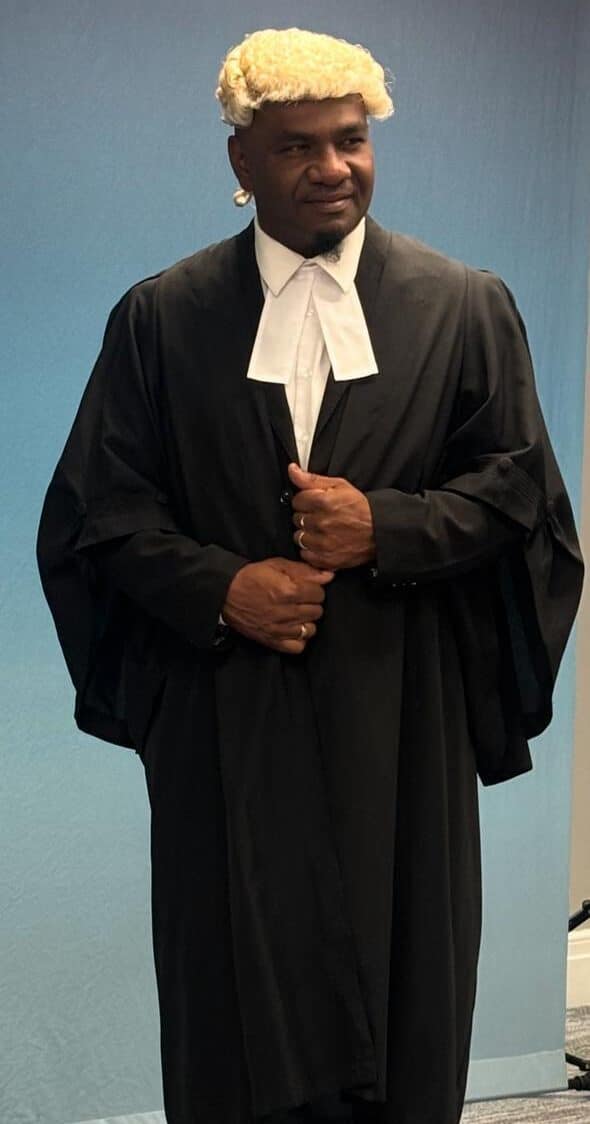

On the judicial front, Antigua and Barbuda’s highest court of appeal is the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in England. This remains a significant remnant of colonialism. On November 6, 2018, the government of Antigua and Barbuda held a referendum to seek voters’ approval to switch to the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) as the country’s final appellate court. The vote fell short of the 67 percent needed. Out of 52,999 registered voters, 17,743 cast ballots, with 9,234 (52.04%) rejecting the proposal to change courts and 8,509 (47.96%) supporting the bill that would have enabled the constitutional change. According to the Daily Observer of November 7, 2018, the main reasons for voting no were that people do not trust the local and regional judiciary; they want to see reforms and improvements in courts, prisons, police stations, and case management locally before considering changing the final appellate court; the Privy Council does not cost the Antigua and Barbuda government anything, so there is no risk of undue influence; and the Privy Council has served well for nearly 200 years, so there’s no need to replace or fix what exists. Arguments for switching to the CCJ included that it would promote the country’s independence; it is too expensive to go to the Privy Council, making it inaccessible; the CCJ’s setup shields it from political interference; the court understands Caribbean culture well, so its judgments would be more culturally relevant; the judges are as qualified as those on the Privy Council; costs are generally lower at the CCJ; and the region needs to develop its own jurisprudence.

As a practicing attorney and without having conducted a scientific poll, I would say that the situation has not changed much regarding voters’ willingness to make the CCJ Antigua and Barbuda’s final court of appeal. It is clear that more effort is needed to educate and persuade the public of the benefits of moving to the CCJ (I try every chance I get to convince skeptics of the utility and wisdom of going to the CCJ). The biggest hurdles are to increase people’s trust in the Caribbean judiciary (many see it as too close to governments) and to demonstrate tangible reforms and improvements in court, prison, and police facilities and procedures. I believe that over the last seven years, there has been some improvement in the management of cases in the courts and in physical facilities (witness the newly renovated Magistrates’ courts). Personally, I have never seen any reason to question the integrity of a judicial officer, and I am confident that if any judge or magistrate falls below the expected standard, there are processes to address it properly. I understand the feelings of the 2018 voters who said no to the CCJ; however, we must dispel the notion that only English judges can deliver fair and equitable justice. In my view, this is an unfortunate remnant of colonialism, particularly the mindset instilled in us over centuries that we are not capable or fully capable of governing ourselves. We must work to decolonize our minds of such thinking. The deconstruction of such colonial discourse involves introducing counternarratives to those portraying colonized peoples as incompetent, dependent, and in need of rescue.

Postcolonial and decolonial perspectives can be applied to almost any major national issue, such as education. Professor Ann E. Lopez, in her book *Decolonizing Educational Leadership – Exploring Alternative Approaches to Leading Schools*, discusses the ongoing, persistent effects of colonialism on Caribbean people, which she calls “coloniality”. Coloniality, she explains, involves long-standing power patterns rooted in colonialism that continue to define culture, labor, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production well beyond colonial administrations. It is sustained through books, academic standards, cultural norms, self-image, personal goals, and many other facets of modern life. Furthermore, coloniality remains in education through its reliance on Eurocentric logic, ways of knowing, and organizational practices at all levels of schooling, often at the expense of alternative epistemologies. Decolonization is the process of undoing coloniality.

Most African countries have established targets to indigenize (or decolonize) their education systems. Indigenization of education involves adapting educational systems, curricula, and teaching methods to reflect and honor the cultures, knowledge systems, languages, and worldviews of indigenous peoples, while still providing students with skills and knowledge for global citizenship and employment. In the African and Caribbean contexts, indigenization is viewed as a transformative way to counter the legacy of colonial education, which often marginalized local cultures and prioritized foreign knowledge and languages. For example, as Jean Kayira discusses in (Re)creating spaces for uMunthu: Postcolonial theory and environmental education in southern Africa, integrating indigenous science into the primary school science curriculum in Malawi can be achieved by teaching mechanics concepts like gravity, acceleration, and projectile motion through indigenous technologies, such as the bow and arrow or the catapult. It is vital for us in the Caribbean to consider our own traditional technologies, like the spinning “top.” Similar to African knowledge systems, Caribbean systems are rooted in tradition and cultural practices. Decolonizing the curriculum is a major topic in educational conversations, requiring thorough discussion and analysis, which this article does not have space to cover.

To offer an alternative to Western ideology, I will conclude with an explanation of the sub-Saharan African philosophy or worldview of Ubuntu (or uMunthu in the Chewa language of Malawi). Its name originates from the Nguni Bantu languages of Southern Africa and is often expressed as “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu,” which translates to “A person is a person through other people.” This philosophy emphasizes the interconnectedness of all humans and highlights values such as compassion, respect, generosity, and community. Jean Kayira states that it is rooted in African humanism, communal customs, and traditional values of mutual respect for one’s fellow kinsmen, which involves humaneness, care, understanding, and empathy. At its core, Ubuntu promotes the idea that an individual’s humanity is deeply connected to the humanity of others, and that personal well-being depends on the well-being of the community. This contrasts with the individualistic approach promoted by the French (Western) philosopher Descartes, exemplified in his famous saying ‘I think, therefore I am’; whereas Ubuntu affirms, ‘I am because we are, and because we are, therefore, I am.’ African philosophy underscores the importance of community over individualism. Ubuntu influences many aspects of life in African societies, from daily interactions to governance and social structures. In families and villages, decisions are often made collectively. Elders serve as custodians of wisdom, and the well-being of the group takes precedence. Ubuntu also underpins traditional justice systems, which focus not only on punishment but, more importantly, on reconciliation and restoration.

I believe that Ubuntu is a good philosophy to adopt in the Caribbean. Indeed, it is in our African “DNA”.

About Dr. Lenworth W. Johnson:

Dr. Lenworth Johnson is a chartered accountant and an attorney-at-law, as well as a

former member of the Senate, the Upper House of Parliament in Antigua and Barbuda. In

2024, he graduated from the University of the West Indies with the degree of Doctor of

Education. Dr. Johnson is a member of the Antigua and Barbuda Reparations Support

Commission.

Advertise with the mоѕt vіѕіtеd nеwѕ ѕіtе іn Antigua!

We offer fully customizable and flexible digital marketing packages.

Contact us at [email protected]

Related News

ABEC pays tribute to the late Sir Gerald Watt KC, former Chairman of ABEC

VIDEO: Turner calls on men to stop abusing women in Antigua and Barbuda

UPP Congratulates Kelton Dalso on Call to the Bar of England and Wales